America's Big Open Was Anything But Lonely Or Empty

ALONG WITH INDIGENOUS PEOPLE, NATIVE ANIMALS LARGE AND SMALL ONCE COVERED NORTH AMERICA'S PRAIRIES—AND IN SOME PLACES, THEY COULD AGAIN

Bighorn sheep on the Northern Range grassland in Yellowstone National Park. Photo by Joel Berger CC BY-ND

CC BY-ND

Bighorn sheep on the Northern Range grassland in Yellowstone National Park. Photo by Joel Berger CC BY-ND

CC BY-ND

Bighorn sheep on the Northern Range grassland in Yellowstone National Park. Photo by Joel Berger CC BY-ND

IN THE GRIP OF WINTER AND EARLY SPRING, THE NORTH AMERICAN PRAIRIES LOOK DECEPTIVELY BARREN. But many wild animals have evolved through harsh winters on these open grasslands, foraging in the snow and sheltering in dens from cold temperatures and biting winds.

Today most of our nation’s prairies are covered with the amber waves of grain that Katharine Lee Bates lauded in “America the Beautiful,” written in 1895. But scientists know surprisingly little about today’s remnant biodiversity in the grasslands – especially the status of what we call “big small mammals,” such as badgers, foxes, jackrabbits and porcupines.

Land conservation in the heartland has been underwhelming. According to most estimates, less than 4 percent of the tallgrass prairie ecosystem that once covered some 170 million acres of North America is left. And when native grasslands are altered, populations of endemic species like prairie dogs shrink dramatically.

Together, we have more than 60 years of experience using field-based, hypothesis-driven science to conserve wildlife in grassland systems in North America and across the globe. We have studied and protected species ranging from pronghorn and bison in North America to saiga and wild yak in Central Asia. If scientists can identify what has been lost and retained here in the US, farmers, ranchers and communities can make more informed choices about managing their lands and the species that depend upon them.

Two harsh centuries of settlement

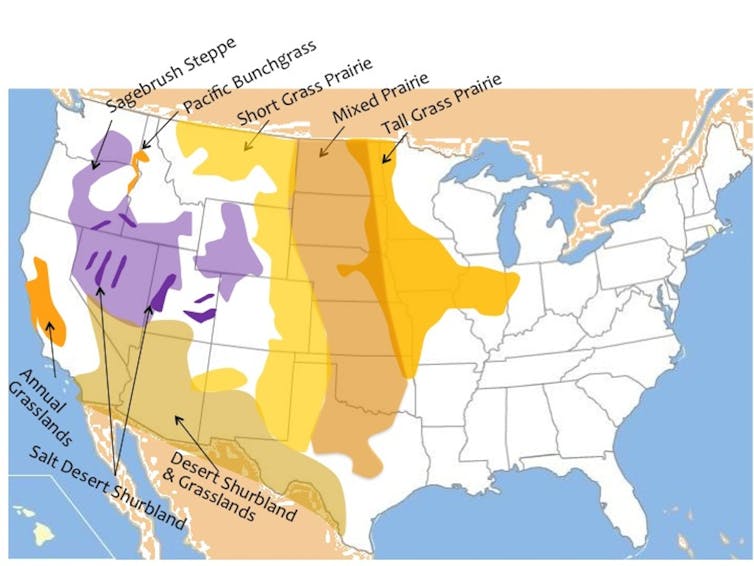

North America’s prairies stretch north from Mexico into Canada, and from the Mississippi River west to the Rocky Mountains. Grasslands also exist in areas farther west, between the Rockies and Pacific coastal ranges.

When Thomas Jefferson approved the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1803, this territory was home to Native Americans and abundant wildlife. Vast, unbroken horizons of contiguous grasslands supported millions of prairie dogs, pronghorn, bison and elk , and thousands of bighorn sheep. Birds were also numerous, including greater prairie-chickens, multiple types of grouse and more than 3 billion passenger pigeons.

, and thousands of bighorn sheep. Birds were also numerous, including greater prairie-chickens, multiple types of grouse and more than 3 billion passenger pigeons.

Lewis and Clark kept detailed records of the plants and animals they encountered on their three-year journey. Their journals describe grizzly bears and wolves, black-footed ferrets and burrowing owls, sage grouse and prairie chickens. Sources like this and John James Audubon’s “Birds of America,” published between 1827 and 1838, confirm that before European settlement, North America’s prairies teemed with wildlife.

Pronghorn, which Lewis and Clark called "speed goats," under the shadow of Wyoming's Wind River Range. Photo by Joel Berger, CC BY-ND

That changed as European immigrants moved west over the next hundred years. Market hunting was one cause, but settlers also tilled and poisoned, fertilized and fenced the land, drained aquifers and damaged soils.

As humans altered the prairies, bison disappeared from 99% of their native range. Prairie dogs, black-footed ferrets, wolves and grizzly bears followed the same sad course.

In the mid-20th century, conservationists began fighting to protect and restore what remained. It isn’t surprising that wildlife agencies and conservation organizations focused on targets that were big, famous and economically important: Birds for hunting, deer for dinner and fisheries for food and sport.

Some efforts succeeded. Montana has retained every species that Lewis and Clark observed there. In 2016 Congress passed legislation declaring bison the U.S. national mammal, following various restoration initiatives in places such as the Wichita Mountains of Oklahoma and the Tallgrass Prairie Preserve in the Flint Hills of Kansas.

Pronghorn antelope, which Lewis and Clark called “speed goats,” have rebounded from fewer than 20,000 in the early 20th century to some 700,000 today, ranging across grasslands from northern Mexico and Texas to North Dakota, Montana and southern Canada.

The Joseph H. Williams Tallgrass Prairie Preserve in Oklahoma, see video above, is a complex environment harboring a rich diversity of plants and animals

But elk remain rare on the grassy savannas, as do prairie dogs and wild bison. North American grassland birds – larks and pipits, curlews and mountain plovers – are in decline or serious collapse. Introduction of nonnative exotic fish, reduced water flows in prairie rivers and streams due to agriculture, and declines in water quality and quantity have decimated native fish species and aquatic invertebrates, such as freshwater mussels, in the waterways of grassland ecosystems.

Where the animals still roam

In contrast to North America, other regions still have large intact grasslands with functional ecosystems. White-tailed gazelles and khulan (Asiatic wild ass) still move hundreds of miles across the vast unfenced steppes of Mongolia. White-eared kob, a sub-Saharan antelope, travel hundreds of miles every year across a North Dakota-sized swath of southern Sudan in one of Africa’s longest land migrations.

Chiru (antelope) and kiang (large wild asses) maintain their historical movements across the vast Tibetan plateau. Even war-torn Afghanistan has designated two national parks to ensure that snow leopards, wolves and ibex can continue to roam.

Knowledge gaps impede conservation

Conserving native species on American grasslands has moved slowly because this region has been so compromised by land conversion for farming and development. What’s more, despite technological innovations and powerful analytical tools, scientists don’t have realistic estimates today of abundance or population trends for most vertebrate species, whether they are mammal, bird or fish.

Measuring remnant diversity is a first step toward deciding what to prioritize for protection. One way we’re doing this is by posing simple questions to families who’ve lived out on these lands for multiple generations. One Montana rancher told us the last porcupine he saw was —well, he couldn’t remember, but they used to occur. Another, in Wyoming, said it had been perhaps two decades since he had last seen white-tailed jackrabbits, a species once common there.

From Colorado to New Mexico and the Dakotas to Utah, responses are similar. Across the region, the status of species like foxes, porcupines, white-tailed jack rabbits, beavers, badgers and marmots is punctuated by question marks. Continent-wide trends remain a mystery.

The good news is that national parks have inventory and monitoring programs that make it possible to assess trends more comprehensively for some of these species. Citizen scientists are helping by reporting occurrences of species such as black-tailed jackrabbits. As scientists delve further into databases, patterns of species retention or loss should become clearer.

For example, our work on white-tailed jack rabbits revealed that decades ago they were abundant in the valleys in and around the Tetons of northwest Wyoming and spanned Yellowstone National Park’s northern range. However, by the year 2000 they were absent from the Tetons and occupied only a small area of Yellowstone.

The U.S. has a history of protecting its majestic mountains and deserts. But in our view, it has undervalued its biologically rich grasslands. With more support for conservation on the prairies, wildlife of all sizes – big and small —could again thrive on America’s fruited plains.

Comments

Post a Comment